Not all churchmen in the Farnham area were spotless examples to their congregations, writes Roy Waight.

One example of a rather less than exemplary clergyman was the Revd Richard Stephens. He was appointed curate of Frensham in 1838 by his wealthy father, William Stephens, who had acquired the advowson to ensure his son a living.

Richard Stephens appears to have acted conscientiously until about 1850, apart from a six-month absence from the parish in 1847 which he attributed to a “very nervous and delicate state of health”. By then, however, it was clear that relationships within the parish were becoming strained.

A pamphlet entitled “A Clergyman’s Defence”, which he issued in 1848, suggests that there were serious differences of opinion between him and his parishioners, particularly the gentry among them. It reveals disputes over a wide range of matters — marriage fees, the closing of chapels, the village school, local clothing clubs and the like.

Disagreements intensified and in 1857, 105 parishioners sent a petition to the churchwardens asking them to seek his removal and to approach the Lord Bishop of Winchester, Charles Sumner, for the appointment of a resident clergyman “able and willing to perform the much required parochial visitations which, we lament to say, have been greatly neglected for a very long time passed”.

The wardens appeared before a four-man commission chaired by the rural dean to present their complaints about Stephens. These included sermons that were difficult to hear, errors in the order of service and repeated failures to keep appointments for baptisms, marriages and burials.

On one well-remembered occasion, a body had become putrid owing to delays in burial. On another, Stephens sent a baby away unbaptised, the child dying on the journey home. Parishioners complained that he failed to visit the gravely ill and injured. He was plainly not a popular figure.

He was required by the bishop to appoint a curate to cover his absences. This he did, before going abroad, apparently to seek medical advice. The parishioners were left to manage without him.

About four years later, an anonymous pamphlet appeared in the district — a lengthy document printed in Paris and entitled “Abuse of Power of the Bishop of Winchester”. It had clearly been written by Stephens.

The pamphlet was strikingly abusive. He referred to the “disgraceful, malicious, and vindictive conduct of the bishop” and alleged “episcopal oppression, rapacity of private property scarcely credible in a free, enlightened country”, even likening the Bishop to King Ahab. The bishop, however, was unmoved. Following further disagreements over his stipend, Stephens was sequestered for debt.

The absence of the Revd Stephens created difficulties for the Revd Henry Julius when he attempted to establish the new parish of Rowledge in 1870. The parish was formed from parts of the chapelries of Binsted, Wrecclesham and Frensham.

Julius secured agreement from the curates at Binsted and Frensham, but he was unable to locate the perpetual curate of Frensham — the aforementioned Revd Stephens — who had gone overseas.

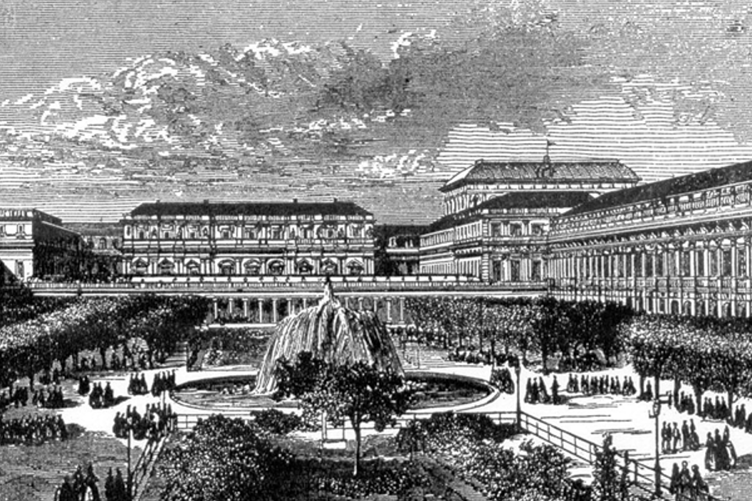

Stephens was eventually traced by Julius in May 1870 living at the splendid Hôtel du Palais in Paris, a magnificent eighteenth-century building close to the Louvre and long regarded as one of the city’s finest hotels. Quite how he afforded such surroundings remains a matter of speculation.

According to Florence Parker, eldest daughter of the first vicar of Rowledge, “The church (at Rowledge) was ready some months before it could be consecrated, as the vicar of Frensham was sequestrated and, although approving the formation of the parish, he refused to sign any documents”.

The Revd Richard Stephens died in 1874, the year Frensham gained its first vicar. Perhaps the absence of firm parochial leadership during the early stages of Rowledge’s creation explains why Frensham continued to contest the boundary until as late as 1875.

Current residents of Frensham may not realise that their lovely church once stood at the centre of a controversy that attracted attention far beyond the village.

For more information about the Farnham and District Museum Society, visit farnhammuseumsociety.org.uk

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.